Internet article transcript

Voicemail: Not Just Another Pretty Voice – New York Times – 1991

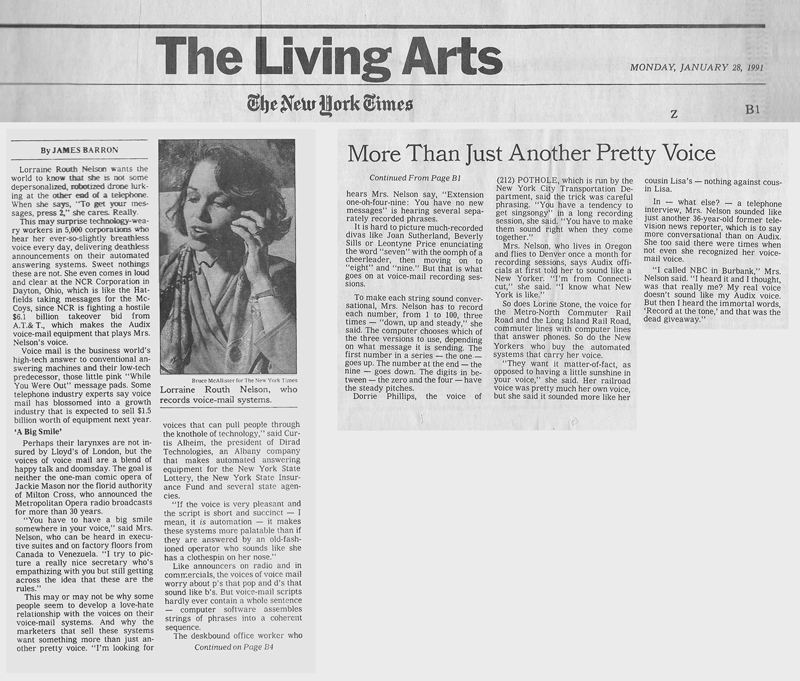

By JAMES BARRON

Published: January 28, 1991

Lorraine Routh Nelson wants the world to know that she is not some depersonalized, robotized drone lurking at the other end of a telephone. When she says, “To get your messages, press 2,” she cares. Really.

This may surprise technology-weary workers in 5,000 corporations who hear her ever-so-slightly breathless voice every day, delivering deathless announcements on their automated answering systems. Sweet nothings these are not.

She even comes in loud and clear at the NCR Corporation in Dayton, Ohio, which is like the Hatfields taking messages for the McCoys since NCR has been fighting a hostile $6.1 billion takeover bid from A.T.& T., which makes the Audix voice-mail equipment that plays Mrs. Nelson’s voice.

Voice mail is the business world’s high-tech answer to conventional answering machines and their low-tech predecessor, those little pink “While You Were Out” message pads. Some telephone industry experts say voice mail has blossomed into a growth industry that is expected to sell $1.5 billion worth of equipment next year.

‘A Big Smile’

Perhaps their larynxes are not insured by Lloyd’s of London. But at NCR — or (212) POTHOLE or the Metro-North Commuter Rail Road — the voices of voice mail are a blend of happy talk and doomsday. The goal is neither the one-man comic opera of Jackie Mason nor the florid authority of Milton Cross, who announced real opera on the radio for more than 30 years.

“You have to have a big smile somewhere in your voice,” said Mrs. Nelson, who can be heard in executive suites and on factory floors from Canada to Venezuela. “I try to picture a really nice secretary who’s empathizing with you but still getting across the idea that these are the rules.”

This may or may not be why some people seem to develop a love-hate relationship with the voices on their voice-mail systems. And why the marketers that sell these systems want something more than just another pretty voice. “I’m looking for voices that can pull people through the knothole of technology,” said Curtis Alheim, the president of Dirad Technologies, an Albany com pany that makes automated answering equipment for the New York State Lottery, the New York State Insurance Fund and several state agencies.

“If the voice is very pleasant and the script is short and succinct — I mean, it is automation — it makes these systems more palatable than if they are answered by an old-fashioned operator who sounds like she has a clothespin on her nose,” Mr. Alheim said.

Separately Recorded

Like announcers on radio and in commercials, the voices of voice mail worry about p’s that pop and d’s that sound like b’s or t’s. But voice-mail scripts hardly ever contain a whole sentence — computer software assembles strings of phrases into a coherent sequence.

The deskbound office worker who hears Mrs. Nelson say, “Extension one-oh-four-nine — You have no new messages,” is hearing several separately recorded phrases.

It is hard to picture much-recorded divas like Joan Sutherland, Beverly Sills or Leontyne Price enunciating the word “seven” with the oomph of a cheerleader, then moving on to “eight” and “nine.” But that is what goes on at voice-mail recording sessions.

A Choice of Pitches

To make each string sound conversational, Mrs. Nelson has to record every number, from 1 to 100, three times — “down, up and steady,” she said. The computer chooses which of the three versions to use, depending on what message it is sending. The first number in a series — the one, for example — goes up. The number at the end — the nine — goes down. The digits in between — the zero and the four — have the steady pitches.

Dorrie Phillips, the voice of (212) POTHOLE, which is run by the New York City Transportation Department, said the trick was careful phrasing. “You have a tendency to get singsongy” in a long recording session, she said. “You have to make them sound right when they come together.”

Mrs. Nelson, who lives in Oregon and flies to Denver once a month for recording sessions, says Audix officials first told her to sound like a New Yorker. She has since smoothed out some of that hard-edged big-city sound because people retrieving their messages found it less than pleasing. “I’m from Connecticut,” she said. “I know what New York is like.”

Sounds Like Her Cousin

So does Lorine Stone, the voice for Metro-North and the Long Island Rail Road, commuter lines with computer lines that answer phones. So do the New Yorkers who buy the automated systems that carry her voice.

“They want it matter-of-fact, as opposed to having a little sunshine in your voice,” she said. Staten Island transit officials, for whom she has been recording bus instructions, wanted her to sound even more matter-of-fact than she did on the L.I.R.R. system. Her railroad voice was pretty much her own voice, but she said it sounded more like her cousin Lisa’s — nothing against cousin Lisa.

In — what else? — a telephone interview, Mrs. Nelson sounded like just another 36-year-old former television news reporter, which is to say more conversational than on Audix. She too said there were times when not even she recognized her voice-mail voice.

“I called NBC in Burbank,” Mrs. Nelson said. “I heard it and I thought, was that really me? My real voice doesn’t sound like my Audix voice. But then I heard the immortal words, ‘Record at the tone,’ and that was the dead giveaway.”